- Introduction

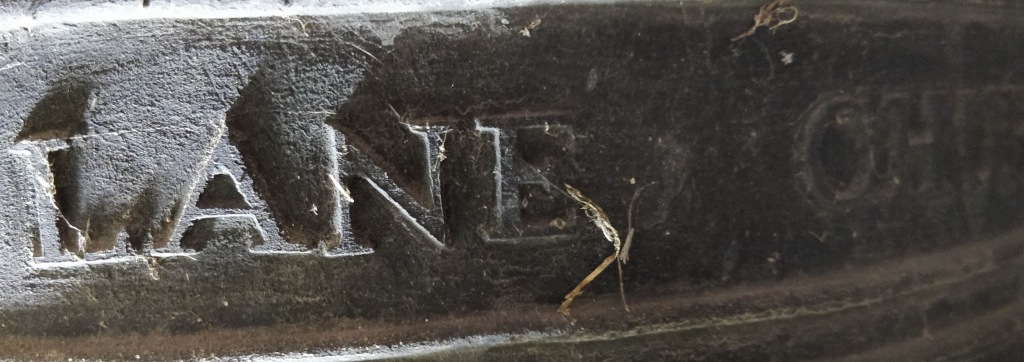

- Bell 1

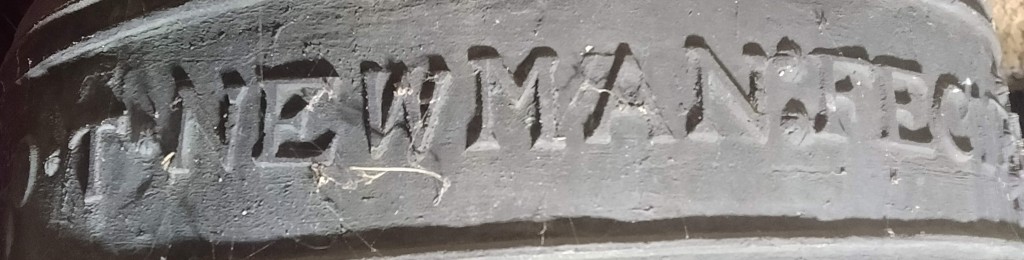

- Bell 2

- Bell 3

- Bell 4

- Bell 5

- Summary of Deopham Bells

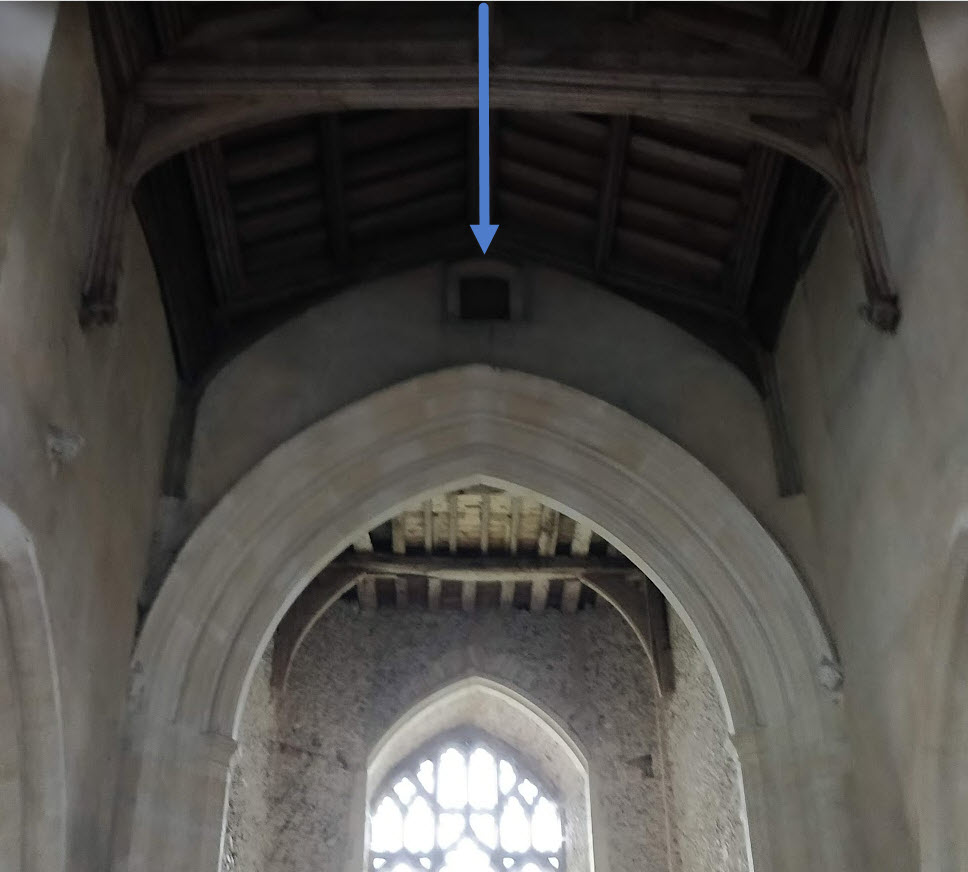

- A Practicality

- A Misunderstanding

- Architect recommends restriction on use of bells

- A Postscript

- Notes

- Bibliography

Introduction

By the time that the tower at Deopham church was constructed, large cast bells had become well established socially as a means of:

- Rousing the people in a summons to mass;

- Alerting the community for some secular purpose such as war or other danger;

- Marking high points in the mass, linking those outside the church to what was going on inside;

- Enhancing celebrations – whether feast days or communal ceremonies;

- Expressing the village’s status by means of the number and quality of the bells;

- Announcing a death.

Supernaturally, bells had further become important to their communities since they:

- were credited with the power to drive away thunder, thunderstorms and tempests;

- protected the space of a community from all sorts of threats on account of the fact that demons, responsible for plagues and diseases, were horrified at the sound of bells and were driven away;

- summoned angels (see the naming of Bell 5 below): the sound waves emanating from the bells opened up a passage for the angels.

Bell 5 (see below) dates from around 1380; John Crennok left money for the bells in 1473, with another bequest in 1488.1 Since both these dates are after that of Bell 5, it is reasonable to assume that the church eventually had three bells in medieval times. This would have been normal for larger towers of that period.

The purge of all things Catholic during the reign of Elizabeth I legislated that all ringing and knolling of bells shall be utterly forborne at that time, except one bell at convenient time to be rung or knolled before the sermon.2 There is no record of what happened to the bells removed as a result of this injunction. Generally they ended up being sold either to be melted down for ammunition or sold overseas. Henry Spelman, clearly opposed to the reforms at this time, wrote:

When I was a child … I heard much talk of the pulling down of bells in every part of my country, the county of Norfolk, then common in memory; and the sum of the speech usually was, that in sending them over sea, some were drowned in one haven, some in another, as at Lynn, Wells, or Yarmouth.3

Only Bell 5 survived at Deopham – presumably to be knolled before the sermons!

In the eighteenth century four new bells were installed in addition to the one surviving medieval bell giving the tower a peal of five bells. These used to be rung by being swung so that the clapper struck the inside of the bell. Only one bell can now be sounded and that bell is fixed with a clapper that strikes the outside rim.

Bell 1

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

The inscription is:-

THO OSBORN FECIT 1781 THOS ROWING AND JOHN LANE CHURCH WARDENS

FECIT = Made it.

There is a gravestone in the churchyard (at location A66) which is inscribed:

To the memory of THOMAS ROWING late of Deopham who departed this life October 11th 1781 aged 55 years.

John Lane was elected constable by the Court of Deopham Hall in 1777, and is recorded in an 1807 survey as the owner of a one acre pightle.

As the smallest bell, this is known as the treble bell.

Photos: G. Sankey, April 2023

Bell 2

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

The inscription is:-

* T * NEWMAN * FECIT JONATHAN DEY & ROBERT * MEEK CW * 1740 *

FECIT = made it; CW = Church Wardens

Jonathan Dey is listed in the register of burials as being buried by William Evans, the Curate, on February 4th 1742.

There is a brief biography of Robert Meek here.

Photos: G. Sankey, April 2023

Bell 3

Photo: G. Sankey, August 2011

The inscription on this bell is

THO NEWMAN MADE MEE 1713

This is the only bell that can still be sounded.

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

Bell 4

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

The inscription on this bell is

THO NEWMAN MADE MEE 1713

Photos: G. Sankey, April 2023

Bell 5

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

This bell has traditionally been dated to around 1380 and ascribed to “Unknown London Foundry”. There is no date inscribed on the bell itself, so the determination of its age has to be based on other bells that show similar characteristics. Neil Thomas, via the Norwich Diocesan Association of Ringers, has written in an email that:

… the consensus seems to be that it was likely cast by an unknown predecessor of William Dawe or less likely one of Dawe’s very early bells.

The most similar bell is at East Ham St Mary, the stops are the same but with the inscription to Gabriel rather than Rafael and ‘cisto’ spelt ‘sisto’.

Dawe began founding around 1381 hence the date of circa 1380.

Other similar bells are found at Bredfield St Lawrence Essex, Leyton St Mary London, Shapwick Dorset, Castle Combe Wiltshire, and formerly at Tollard Royal, Wiltshire the inscription now part of candelabrum at King John’s House on the Rushmore Estate.

The inscription is something of an enigma. It reads:

* DULSIS * CISTO * MELIS * VOCOR * CAMPANA * RAFAELIS

which very roughly means:

I AM CALLED THE BELL OF RAPHAEL SWEET BOX OF HONEY

This clearly makes very little sense!

The bells, on account of their association with angels, were often given the names of the three angels mentioned in the bible – Gabriel, Raphael and Michael. The Gabriel bell would carry the text “I bear the name of Gabriel sent from heaven”. In latin, heaven is “CELIS”. There seems to be a pun here with the Raphael bell referring to honey which is “MELIS” in latin. The CISTO on the Deopham bell is replaced by SISTO on bells elsewhere with a similar message and means “I stand” or “I am”. The Gabriel text quoted also refers to sweet Mary (mother of Jesus).

After a discussion with Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, it seems that the inscription on this Deopham bell means:

I STAND (AM) OF SWEET HONEY [IN SOUND]; I AM CALLED THE BELL OF RAPHAEL

There is at the same time a sub-text saying “I might only be the bell called Raphael, unlike the bell Gabriel who came down from heaven (celis), but all the same I am sweet as honey (melis) like Mary.”

As the largest bell, Bell 5 is known as the tenor.

I AM CALLED

THE BELL

OF RAPHAEL

SWEET

BOX

(although for the latin to be correct this should read CISTA; alternatively, this should have been written as SISTO meaning “I stand”).

OF HONEY

Photos: G. Sankey, April 2023

Summary of Deopham Bells

| Bell | Maker | Date | Note | Diameter | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thomas Osborn, Downham Market | 1781 | D# | 28.81″ | |

| 2 | Thomas Newman, Norwich & Cambridge | 1740 | C# | 31.00″ | |

| 3 | Thomas Newman, Norwich & Cambridge | 1713 | B# | 31.50″ | |

| 4 | Thomas Newman, Norwich & Cambridge | 1713 | A# | 34.88″ | |

| 5 | Unknown London foundry, possibly the predecessor of William Dawe. | c. 1380 | G# | 39.00″ | 12 cwt |

The data for the notes, diameters and weight are from Dove’s Guide for Church Bell Ringers:

https://dove.cccbr.org.uk/tower/11302

A Practicality

In order to raise the bells up the tower, a windlass was used. This can still be seen in the ringing chamber:

Photos: G. Sankey, April 2023

Paul Cattermole describes the Deopham windlass as follows:4

This windlass consists of a cylindrical roller mounted at one end in the tower wall, and at the other end in a stout vertical post; the cable would have passed over a pulley wheel high in the centre of the tower. The mechanical advantage of the machine would be about 1:10, allowing considerable weights to be lifted through the central traps in the lower floors. The Deopham lifting gear has much in common with the mediaeval windlasses in the towers at Salisbury Cathedral, Peterborough Cathedral and Tewkesbury Abbey; and the arrangement of the mortises for the spokes of the hand-wheel is said to indicate a date before the 16th century.

A Misunderstanding

There is an opening in the bell ringing chamber which could give a view down the length of the church were it not currently blocked off with plywood. It has been argued5 that this allowed the bell-ringers to be able to see the altar so that they could ring the sanctus bell at high points of the mass. Munro Cautley5 therefore called these openings “sanctus-bell windows”. However, Dr. Paul Cattermole (who was the Diocesan Bells Adviser from 1978 until his death in 2009) has pointed out6 that in medieval times the bells were being rung from a first floor chamber, so that this opening high up the tower would have been of no use. Cattermole proposes therefore that this feature originally gave access to the cavity between the ceiling and the steeply pitched outer roof. This is borne out by the fact that the top of the present opening is level with the ceiling of the nave, although in the inside of the tower it is clear that the opening used to be much taller. There are also signs in the nave that the roof used to be lower than it is now, in particular the redundant corbels on the south wall.

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

This is what the opening looks like from the nave:-

Photo: G. Sankey, April 2023

Architect recommends restriction on use of bells

The church architect, Cecil Upcher, wrote to the Rev. Gray on December 19th 1952 to advise the outcome of a professional examination of the bells. It was stated that because of the dilapidated condition of the bell fittings and frame, they advised the church should only ring the smallest bell. The cost of repairs was £800 for the bell hanging plus the cost of structural repairs to the tower.

A Postscript

The EDP of May 18th 1962 reported:-

Out of action since the late 1930s, the bells of the 12th century church of St. Andrew’s, Deopham, may never ring again.

Hanging in the 100-ft. tower of the church, the six bells were considered to have one of the finest peals in the county, but a recent estimate of £2000 for repairs has all but destroyed the villagers’ hopes of hearing them again.

In addition to the sum for repair of the bells £2500 is also required for essential repairs to the fabric of the church which dates from 1146.

The Rev. A. F. Castle, Vicar of Deopham, said, “I can see no way of getting £2,000 for the repair of the bells in this small community. It is most unlikely they will ever be heard again in Deopham.”

Notes

- The will of John Crennok of Depham, 1473, is held by the Norfolk Record Office, ref MF30. The 1488 bequest is mentioned in the church guides, but no further information is provided.

- Injunction XVIII.

The full text of the 1559 injunctions is available here:-

https://history.hanover.edu/texts/engref/er78.html - Sir Henry Spelman The history and fate of sacrilege (1895), pg 159

- Paul Cattermole, Church Bells and Bell-ringing. A Norfolk Profile, 1990, pg 75.

- Henry Munro Cautley, Norfolk Churches (1949) quoted by Cattermole.

- Paul Cattermole, Church Bells and Bell-ringing. A Norfolk Profile, 1990, pg 70.

Bibliography

- John L’Estrange The church bells of Norfolk : where, when, and by whom they were made, with the inscriptions on all the bells in the county

- H.B. Walters Church Bells of England.

Pg 268 comments on the transformation of the dedication to Gabriel into that for Raphael. - Nicholas Orme Going to Church in Medieval England

- John H. Arnold and Caroline Goodson Resounding Community: The History and Meaning of Medieval Church Bells

- Sir Henry Spelman The history and fate of sacrilege (1895)

- Alain Corbin Village bells : sound and meaning in the 19th century French countryside (1999). Whilst obviously not directly about Norfolk, Corbin discusses the significance of bells in medieval society generally.

- Paul Cattermole, Church Bells and Bell-ringing. A Norfolk Profile, 1990

| Date | Change |

|---|---|

| 29/4/24 | John Lane was a constable in 1777 |

| 11/3/24 | Updated John Lane details |

| 9/6/23 | Added letter from the architect recommending restrictions on use of bells. |

| 26/4/23 | Published |